Home » We Are All Missionaries

We Are All Missionaries

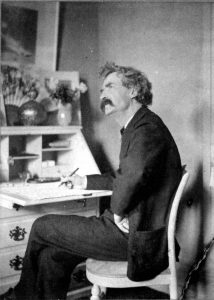

In 1905, Mark Twain scratched the following statement in his notebook. He foresaw the underlying cause for today’s nonprofit logjam:

“We are all missionaries (propagandists of our views),” he quipped. “Each of us disapproves of the other missionaries.”

Even Mr. Twain would likely have argued that the world needs social entrepreneurs, today’s missionaries. Doctors without Borders, World Wildlife Fund, Teach for America, Save the Children all fill great societal gaps.

What Mark Twain railed against was not a social entrepreneur’s do-good instinct, rather the friction we cause each other and our stakeholders by ignoring lessons hard won by other nonprofits.

Ignoring the capacity-building achievements, strategic initiatives – even failures – of others is a mistake.

From a funder’s perspective, when a nonprofit ignores the competitive dynamic it can suffer serious consequences. Nonprofits may underserve their clients because they do things the way they always have – with a full heart but with a singular, perhaps flawed home-grown approach. In the meantime, other similar agencies have won more donor dollars, allowing them to expand and scale, leaving smaller nonprofits to fend for scraps.

Can nonprofits serve their clients in a better way? Can funders get more for their money?

The answer is yes and yes – but not by remaining in a vacuum.

Every nonprofit needs to take a step back, remove itself from the whiteboard and endless round-the-conference-room discussions. One very effective way for a nonprofit to get this reality check and stress test its strategy is to enter the world of informed roleplay and structured argument.

What I am proposing goes far beyond a field scan, a research exercise for the most part. Social agency leaders must acknowledge they have competition and – as best as they can – bring those competing social innovators into the room.

In the business world, corporations might call these roleplay simulations war games. War games, though, suggest the wrong intent and outcome even for companies.

A corporate simulation is not about a zero-sum game, vanquishing your rival. It’s not about “I win, and you lose,” a near impossibility in most situations. Instead, when you run a simulation, your goal is to build a better, more resilient, future-looking strategy. It exposes everyone in the room to hidden opportunities, other players’ strengths, as well as changing market conditions.

Over the past two decades, I have run scores of simulation games for organizations across the globe. At the end of nearly every simulation, executives come away with ah-ha moments, some very subtle but yielding substantial improvements.

Recently, I ran a simulation for one nonprofit straining to reach a national audience, but running into a host of barriers, including funding limitations. The executives and the agency’s board was stuck as to how to move forward.

Questions had piled up over the last couple of years. Which metro area needs our focus? What initiative do we say “no” to? How can we increase our multi-year grant commitments? How do we build capacity, considering the variability of donations and funding cycles? Do we go it alone or do we partner? Should we merge?

The simulation we ran for this group involved over 25 people and included the entire board, the operating executives, as well as a handful of key funders and supporters. Everyone had the best interests of the organization in mind as they divided up into four groups, two competing nonprofits, a funder team, as well as the “home team,” representing the nonprofit.

The simulation involved two rounds, where each team presented its strategy and had to defend that strategy. At the end of the day’s role play, I asked everyone to drop their masks. Going around the room we discussed lessons learned, assumptions realigned, and enlightened comments about rivals formerly dismissed.

We then spent another day with a smaller group, digesting the prior day’s conclusions and distilling the lessons yet further into a relatively short to-do list of strategic moves the organization must make to grow.

Among these were:

- Select one urban area to establish an active presence and invest its precious donor dollars.

- Where to say “no” to opportunities and begin to focus the nonprofit’s activities and its message on what it does best and where it distinguishes itself as different and successful when compared to rival organizations.

- Grow two out of its half dozen programs. We realized that these two programs would help fund all the other efforts but required more manpower and marketing.

- Create a new board structure driven by a need to inject fresh, outside viewpoints.

- Look for a specific type of partner that would complement and benefit from the mutual relationship (we created a shopping list of possible candidates).

The report covered a half-dozen other key points; some were new and creative. The simulation also gave new life to previously suggested ideas that became buried in meeting minutes from past board sessions.

This simulation, along with many others I’ve run all around the globe reinforce a healthy dynamic, a dynamic of open and informed discussion about the world around you. It applies economic logic, and market pressures. It unsticks old, unproven biases. It offers a rationale for why one strategic position may be more successful than another.

I could argue that if Mark Twain read this blogpost, he might change his statement to read, “We are all missionaries. Each of us needs to learn from the other and from the world around us.”